|

|

|

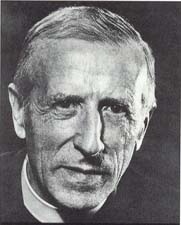

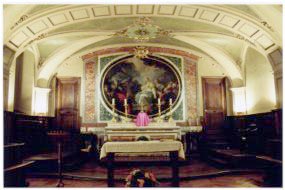

Paul Couturier, who died just over fifty years ago, was born in 1881 in Lyon, the great city where in 1274 the divisions between East and West had for a time been healed. After a time in Algeria, he was ordained in the Society of St Irenaeus in 1906, a company of mission and teaching priests. A graduate in physical sciences he became a teacher at the Society's school founded in the Maison des Chartreux, the dissolved Carthusian monastery, where he remained until 1946.

As a result of an Ignatian retreat in his early twenties Fr Albert Valensin SJ encouraged him to take up some relief work among Lyon's 10,000 Russian refugees, and introduced him to Orthodoxy and a hitherto unknown world of spirituality, theological expression and Church life. Metropolitan Platon Gorodetsky (1803-1891) of Kiev's saying, that 'the walls of separation do not rise as far as heaven', became a principle of Couturier's ecumenical outlook. Then a month's stay with the Benedictine Monks of Unity at Amay-sur-Meuse (nowadays living at Chevetogne in Belgium) formed a second important step towards the realisation of his ecumenical vocation. Strongly influenced by the teaching of Dom Lambert Beauduin, he placed the prayerful celebration of the Church's liturgy - not as a private devotion, but the work of all the Church, lay and ordained - at the heart of his spiritual life. He became an oblate of Amay, taking the name Benoît-Irénée to acknowledge his two prime sources of inspiration. In the years to come he found this spirituality, which had so revived his own Church and the active participation and mission of Catholic lay people, could also embrace Christians of other Churches. All Christians could unite in regular prayer and devotion, each according to their own tradition and insight, for the sanctification of the world and the unity of Christ's people. So was born the idea of 'the Invisible Monastery', a spiritual holy place and community, beyond the earth's 'walls of separation', where God's vision of his Church's unity could be realised and celebrated in prayer, praise, mutual love and humility, for the sake of the world.

Couturier was deeply struck that Jesus' prayer on the night before he died was not simply for his disciples' unity, but that they might be one as the Father and the Son are one, so that the world might believe. He realised that the unity of Christians was therefore a reality in heaven, in God himself, and that overcoming the worldly Church's divisions through penitence and charity would be offer a renewed faith to the whole world. So merely human efforts, methods and timetables would not in the end avail: what was needed was a 'Spiritual Ecumenism', that prays for the unity of Christians 'according to his will, according to his means'.

The power of prayer, and its potential for overcoming separation and the wounds of centuries, lay at the heart of all groups of Christian believers, and so he came to see that, as people grow in sanctity in their different traditions, they grow closer to Christ. If Christians could then be aware of each others' history, spirituality, traditions of faith and worship, their hurts and their glories, they could thus grow closer to each other. The foundations, he realised, would need to be humility, reparation and no little suffering. But if Christians could imitate each other - not just go to each others' services, but embrace each others' spirituality and traditions for their own - the path to holiness in one Church could be adopted and enhance the path to holiness in the others too. This 'emulation' has been described as 'vying with one another' to advance on the path to holiness and to Christ - not mutual admiration, not unfriendly rivalry. but a 'race that is set before us' in which we spur each other on beyond our own small worlds to fresh understanding, to new awareness of Christ and his Church, to a closer bond with him and his people. In the last fifty years we have seen the Abbé's prayer that Christians could all pray the Lord's Prayer together realised. Catholics have adopted many great Protestant and Anglican hymns and chorales. Anglicans and other non-Roman Catholics have taken to heart the Retreat movement, and also embraced the importance for the Orthodox of Icons. The Orthodox have become increasingly influential members of the World Council of Churches, and all now share in a renewed common love of the Scriptures. These are fruits of spiritual emulation.

A third influence on Couturier was Teilhard de Chardin. Both men were scientists, and Teilhard's vision of the unity of creation and humanity expressed in the unity of Christ and the life of the Church appealed both scientifically and spiritually to Couturier. A reasoned consequence for him was that the unity of Christians was the sign for the unity of humanity, and that praying for the sanctification of Jews, Muslims and Hindus, among many others, could not fail but to lead to a new spiritual understanding of God where Christ could at last be recognised and understood. Couturier felt this keenly as he was partly Jewish and had been raised among Muslims in North Africa. It is worth noting that among Couturier's voluminous correspondents were Jews, Muslims, and Hindus, as well as every kind of Christian, all caught up in the Abbé's spirit of prayer, realising the significance and dimensions of prayer for the unity of Christians. Coincidentally, years later Mother Theresa spoke of the considerable number of Muslims who volunteered and worked at her house in Calcutta: 'If you are a Christian, I want to make you a better Christian - if you are a Muslim, I want to make you a better Muslim'. It cannot be denied that what those Muslims were seeing in Mother Theresa was Jesus Christ himself, just as the Abbe attracted so many to prayer across previously unbridgeable divides by his humility, penitence, and joyful charity in the peace of Christ.

2003-2004 also marked the 50th Anniversary of the launch of the Week of Prayer in Morocco as an act of charity and prayer among the people of Islam, a significant milestone in the experiences of today as much as then.

In January 1933, during the Church Unity Octave, Couturier held three days of study and prayer. The Octave had been founded in 1906 by the Reverend Spencer Jones (vicar of Moreton-in-the-Marsh) and Father Paul Wattson of the Friars of the Atonement (when still Anglicans) to pray for the reunion of Christians with the See of Rome. Another pioneer was Fr Ignatius Spencer, the first to promote prayer for Unity on Thursday after the pattern of the Lord's own high priestly prayer the night before he died - he even succeeded in bringing Cardinals Newman and Manning together to write a prayer which was even sanctioned by the English Catholic bishops to this end, though (as it was in Latin) he recommended for lay people that Catholics pray the Hail Mary and Anglicans the Lord's Prayer. After the Friars became Roman Catholic, the observance was extended to the whole Roman Catholic Church in 1916. But Couturier wanted to build on the Octave something which could embrace in prayer those who were unlikely ever to become Roman Catholics but who nevertheless desired the end to separation and the achievement of visible unity. In 1934, Couturier's new form was extended to a whole week, and the modern Week of Prayer for Christian Unity was born.

This title, incidentally, could be a misnomer, as Couturier did not believe in ecumenism as a phenomenon in its own right; nor did he believe in the amalgamation of separate earthly bodies of Churches. One of the 'marks of the Church', unity is an ever present fact of life which has to be discovered, not constructed. So he always called it the Week of Prayer for the Unity of Christians, Christians by whose prayer and convergence in holiness, each loyally according to his or her own tradition and Church discipline, the Unity of the Church would at last become visible.

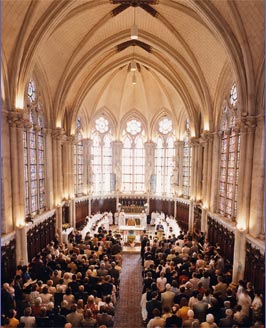

The annual celebrations in Lyon, with their important speakers and high level ecumenical participation, became famous, attracting attention throughout Europe as a significant breakthrough. They coincided with the important theological work of Yves Congar, whose thinking in the field was to become so influential in Vatican II's renewed teaching on ecumenism. In 1936, the Abbé Couturier organised at Erlenbach in Switzerland the first interconfessional spiritual meeting, mainly of Catholic clergy and Reformed pastors, which was to meet in fellowship for many years and directly contributed to the foundations of the World Council. Two visits to England in 1937 and 1938 completed the Abbé's initiation into ecumenism with his discovery of Anglicanism, not least through his encounter with the Anglican religious communities and episcopal, sacramental life in a Church of the Reformation. Anglicans, he hoped, would have a special role in realising the ideals of emulation and the Invisible Monastery from their own experience as a Church with many different, even divergent, traditions in a country with many separated Churches, including his own Roman Catholic community.

The scheme for the Week of Prayer which he devised, held all these contacts and friendships together, in a prayer that all Christians, all humanity, should be sanctified and converge in Christ along paths of charity and mounting expectation with the consummation and revelation of Christ's truth in the unity for which he prays.

During the war, largely on account of his extensive international contacts, Couturier was imprisoned by the Gestapo. This broke his health, but he identified his suffering and heart disease as a cross which he was being called to take up in the service of the unity of Christians. He continued to write letters, to pray the liturgy of the Church, to make arrangements for the Week of Prayer and to sustain friendships and contacts around the world which could lead to unity. He lived to rejoice in the foundation of the World Council of Churches in the aftermath of a broken and chastened Christendom after World War II. And though his own Church did not join the new body, his hope that Rome could lead an appeal for convergence was heard by Pope Pius and doubtless informed the new outlook of the forthcoming but as then unforeseen Council. In 1952, a year before his death, the title of Archimandrite in the Patriarchate of Antioch was bestowed on him in recognition of his work for ecumenism. He died in Lyon on the 24th March 1953. At his funeral, the Archbishop of Lyons, Cardinal Gerlier, hailed him as the Apostle of Christian Unity. His immense spiritual vision, his work and his prayer continue to inspire.

Cardinal Gerlier's Tribute at the Abbé Couturier's Funeral Mass